Tortured, emaciated figures lost in thought in a dizzying space, melting backgrounds and skin resembling decay.

Retaining the same shock factor a century on, the troubling works of Egon Schiele continues to intrigue art lovers.

In a short life, he became a pioneer of the Expressionist movement while making strides through shocking, bold and sexual works.

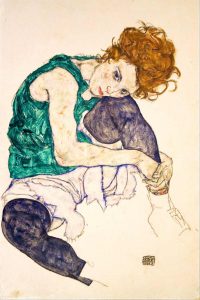

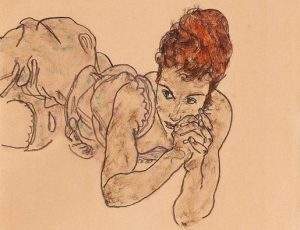

Tension, anxiety and sexuality are conveyed in a distinctive linear manner, with figures often contorted in an unusual ways to trouble the viewer.

The distinctive style of Egon Schiele developed over his brief career that which amassed over three thousand drawings in a style that challenged beauty norms.

His life leads to a disturbing read with strange motives shaping his erotically and psychologically charged art.

The painter, draughtsman and printmaker developed his own unique language that expresses feelings of fear, isolation and loneliness in a distinctive manner.

Madness, bold and radical, Schiele has all the components to make a striking read for the third edition of An Focal Art Club.

Hailing from Tulln, Lower Austria, a young Schiele was heavily influenced by his father who worked as a stationmaster. His father’s occupation spurred a love of trains, an obsession which manifested in the many drawings he made of them. His father destroyed his fanatical sketchbooks, scorning the idea of his son becoming an artist.

When Schiele was fifteen, his father died. This left a lasting scar on Schiele’s work which often explored overwhelming loneliness and tension.

Aged 11, Schiele began attending secondary school in Austria. He was poorly received, with a shy brooding demeanour deterring any friendships. However, the young boy took to drawing and his gift was further encouraged by his maternal Uncle.

He studied painting and drawing at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna but soon became disillusioned with the conservative rules of the school and left after only three years.

His early influences came from the Jugendstil movement and the German Art Nouveau.

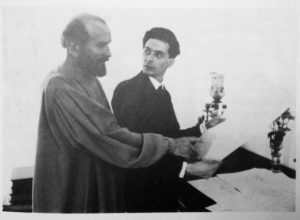

It was meeting Gustav Klimt in 1907 that marked a turning point in the artist’s practice. The two shared drawings, with Klimt spotting talent in Schiele.

Klimt had a passion for mentoring and gave Schiele a chance at his first exhibition. He also introduced Schiele to a young Wally Neuzil, who became a muse for many of his works.

Schiele would be heavily influenced by the composition and linearity of Klimt’s works, however rejected Klimt’s decoration for muted, earth tones to create a more expressionist style, evoking imagery of decay.

He also grew to feel restricted by conventional subject matter in paintings and began to explore painting human sexuality in an uncompromising, bold manner.

His new life caused an extreme, morally corrupt lifestyle.

This led to his imprisonment for seducing a minor, an experience that he documented in his figurative watercolours while serving his 24-day sentence.

The artist left his studies to join a group for other disillusioned creators named the Neukunstgruppe. Here, Schiele discovered the works of Munch and Van Gough and incorporated aspects of their style into his own work.

He continued to exhibit with the Neukunstgruppe before holding his own solo show in Galerie Hans Goltz in 1913.

He married Edith Harms before being drafted into the Austrian army where he continued to produce work while acting as a guard at a Russian Prisoner of War Camp. As an officer, he exhibited in Dresden and Munich alongside painting the Russian prisoners in a makeshift studio at the camp.

His work continued to evolve at a startling pace, creating his own unique language while challenging the standards of the world around him through evocative, vulnerable imagery.

It was a critically acclaimed solo show in Vienna that finally brought the artist financial success. This marvelled display included an interpretation of The Last Supper where he portrayed himself as Christ. After finally achieving resounding acclaim, tragedy struck.

His wife Edith was six months pregnant when she fatally contracted the Spanish flu. Schiele died a mere three days later, leaving behind him a legacy that challenges, shocks and inspires.

Gustav Klimt was the main influence on Schiele’s practice, acting as both a friend and mentor. He mirrored his erotically charged distorted images alongside attempting to convey the inner emotions and psyche of their sitter on the canvas.

The two diverged from Klimt’s bright and pattered style for a more gritty, darker covey which led to Schiele developing the unsettling Expressionist form.

His primary mediums were pencil, gouache and watercolour painting.

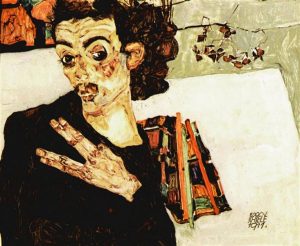

Bizarrely, Schiele frequently produced self-portraits in his characteristic revealing pose, uncompromising and unprecedented in the European art world at the time.

His portraits are disturbing creations, legs without feet, a body exposed, a hidden face or glowing red eyes, contorted to covey agony, vulnerability, the fragility of human life.

This unconventional treatment of the human form was an attempt by the artist to unveil the human psyche beneath an appearance.

He was obsessed with his own image and famous for his narcissism, with a striking emotional treatment of all his self-portraits marked with bold lines.

Schiele developed foreshortening to distort his subject’s limbs in order to further discomfort nervous, isolated figures lost in space. Portraits are often placed in indecipherable, dizzying environments to represent disorientation.

His portraits provide a harrowing depiction of psychological distress through the use of line and colour, rid of inhibition or convention.

A radical attribute of Schiele’s style is his frequent depictions of sitters from a height. The subject appears to be toying for space in a shrinking canvas, vulnerable and insignificant against the powerful perspective of the viewer.

Women are often treated as hyper-sexualised, a controversial approach that led to outrage at his early exhibition for their bold and aggressive treatment.

Schiele also produced a series of quasi-surreal landscapes influenced by his travels throughout Europe. Here his style carries through, with a convergence of using a bird-eye perspective and bold contours.

Hermits (1912)

A tribute to his mentor and muse, Gustav Klimt, this is a rare composition for Schiele as it contains two figures, both wearing Klimt’s trademark black caftans. Klimt appears to be in the wake of the forefront figure Schiele, as if consumed by a younger more powerful artist. It appears to be Schiele is a newer form of his primary influence, with both elongated figures depicted as dark and looming observers.

Death and the Maiden (1915)

This painting is influenced by the medieval concept of the Dance of Death and marks the end of his relationship with Wally Neuzil, memorialising the end of their affair and signifying the death of true love.

Portrait of Wally (1912)

This portrait is of his lover and model Walburga“Wally”Neuzil. The two were introduced to each other by Klimt and she fled with Schiele to a small village in Bohemia. Oversized bright blue eyes are magnified by a masterful use of geometry to create a feeling of intimacy, magnified by complementary colours.

Self Portrait with Black Vase (1911)

His trademark challenging perspective displays his treatment of the hand, with thin figures spelling tension. The interior and jarring placement of his self-portrait creates disorientation. Some interpretations say the colour pays tribute to his mentor Klimt, while the black represents his own practice which matches the colour, suggesting the two were equals.

An Article- Five Things to Know: Egon Schiele, Tate. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-liverpool/exhibition/life-motion-egon-schiele-francesca-woodman/five-things-know-egon

A Podcast- The Lonely Palette Podcast, Episode 29: Egon Schiele’s Nude Self Portrait (1910)

A Book- Egon Schiele by Jane Kallir, Thames & Hudson Ltd

![]()