“To me, the trick is to seduce the viewer. If you can get the viewer to look at a work of art, then you might be able to give them some sort of message.”

Still practicing at the age of 93, Betye Saar is finally receiving global recognition for her prolific career creating politically charged folk art.

Her use of symbolic and surreal imagery makes her a leading figure in the folk art aesthetic and a master of the medium of assemblage.

Famed for recontextualising icons of African-American folklore for social commentary, Saar tackled the male-dominated medium of three dimensional collage to explore themes of feminism, race and oppression.

Highly spiritual, her pieces are not only intriguing but innovative, with her sustainable attitude towards materials leading to striking pieces.

Her work is rooted in nostalgia with a political motive, imploring the viewer to question topics relating to identity and memory.

From Los Angeles, Saar attended the University of California studying design, before furthering her education by studying printmaking and education at California State University.

Her early pieces were mainly etchings and intaglio before becoming fascinated by the practice of assemblage, creating three-dimensional collages from everyday items.

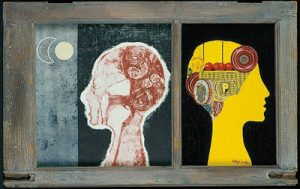

Saar began assembling works made from household items, incorporating themes of religious imagery and cosmology into her early pieces.

Her art uses items that represent the past appropriated into different contexts.

Saar’s work became more radicalised after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, with domestic items like a washboard and racist propaganda employed to depict her lived reality and comment on themes of racism, identity and segregation.

As one of the first female assemblage artists to emerge onto the art scene, her work often comments on feminism and the realities of being a marginalised artist.

She became a member of the Black Arts Movement, motivated to confront the white-dominated narrative in the American art world.

While Saar’s talents were immense, she was treated as an outsider from the rest of the art community due to being outside the artistic hotspot of New York City in the 1960s.

However, undeterred by this, Saar continues to practice with her prolific career spanning six decades.

During her career, Saar became a teacher at the University of California and Parson-Otis Institute.

Still based in California, Saar has two daughters, Alison and Lezley.

Saar’s main preoccupation is with the value of objects and how they can be used to give context, documentation and meaning to her lived reality.

Using symbols such as Aunt Jemima and Uncle Tom, Saar adapts these stereotypes from advertising to convey central themes such as mysticism and nostalgia.

Preoccupied with contemporary identity, her assemblages and collages contain items to represent the past merging with the future.

Saar’s first focus was on printmaking and etching using stamps, stencils before moving to collages inspired by assemblage artists Joseph Cornell and Simon Rodia.

Sarr mixes symbols of domestic life with traditional African imagery to depict the African-American oppression.

In her early assemblages, Saar lined boxes with her prints and objects, using materials such as window frames to create her pieces.

Feminism is also a strong theme throughout Saar’s work, with household items often used to represent women’s oppression, trapped within the confines of a domestic environment.

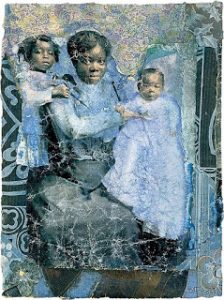

Saar’s work often uses photographs, clothing, and gloves to create her pieces.

During the late 1970s Saar began to move onto larger projects, creating room-size installations that required the viewer to leave an item to contribute to the work, a practice often used in African culture.

While often employing everyday materials, Saar claims that she also recycles the same feelings and emotions that inspire her work that often relate to feelings of oppression in a segregated America.

There is rich multiculturalism to her work, with the assemblages containing items and symbolism from across the globe.

Her assemblages can contain material she required markets.

Her work is now part of the permanent collections of over 60 galleries and museums.

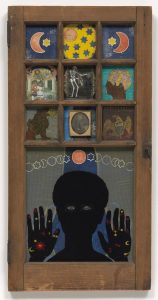

Black Girls’ Window (1969)

This is an autobiographical assemblage, where a black girl presses her face against the pane, with priminant blue eyes gazing out at the viewer from behind the glass.

Floating hands symbolise the moon and stars, with the arrangements at the window frame symbolising astrological signs.

The work marks the artist’s move from printmaking to assemblage, with a window frame isolating nine painted vignettes. Created the year of her divorce, this piece addresses the artist’s personal, public and spiritual existence.

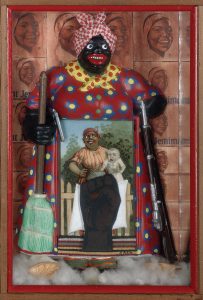

The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972)

Equipped with a hand grenade and a rifle, The Mammy figure is an assemblage with Saar’s characteristic trait of turning a once derogatory symbol into a politically charged statement.

Mammy caricature once appeared on everything from kitchenware, toys and prints and is one of the most recognisable and enduring stereotype caricatures in America. The symbol stands for eradicating the black experience, depicting the servant as placid and content despite her oppressed status in society.

Placed in front of syrup labels, the figure is now a warrior against stereotypes and imager and also the physical violence experienced by black Americans.

Spirit Catcher (1977)

Created from bamboo, bones, feathers, shells and wicker, this piece was inspired by the artist’s first visit to Africa. Tibetan spirit traps were placed on roofs to ward off evil, recognised by their spindle-like structure.

Keep for Old Memoirs (1976)

Family history is a reoccurring theme throughout Saar’s practice, and this piece includes photographs and letters from the collection of her Aunt Hattie.

The items represent nostalgia and demonstrates how objects can represent a lifetime.

An Article:

Betye Saar: the artist who helped spark the black women’s movement. Nadja Sayej, The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/oct/30/betye-saar-art-exhibit-racism-new-york-historical-society

A Video:

![]()