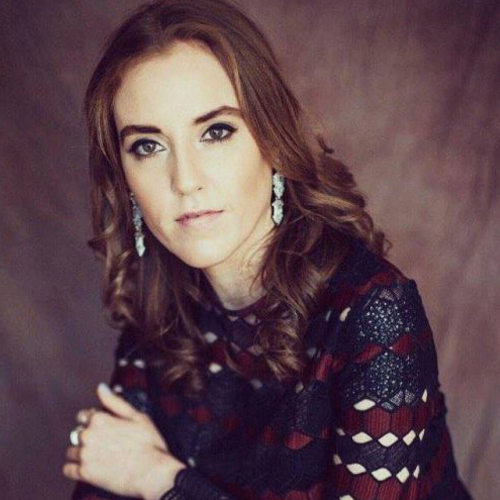

By Nicole Glennon

When Louise O’Neill walks into the room she smiles brightly and extends her hand for a handshake. She laughs when I tell her I’m eager to get started and jokes that she can only be a “massive disappointment.”

O’Neill is back at the University of Limerick for the second time this semester as part of the college’s “One Book One Campus” initiative.

A month ago she discussed her book Asking For It to a packed audience in the Kemmy Business School, and this time around she’s here to engage in conversation with Lawrence Cleary, co-director of the Regional Writing Centre, about her writing process. Both sessions ended in an audience Q&A, where it was easy to see that she has amassed a following of admiring young women.

Unsurprisingly, the Clonakilty native is increasingly popular among this demographic and has found herself something of a spokesperson for the feminist movement in Ireland. Both of her novels have been heralded as feminist YA fiction and usually found at the centre of discussions surrounding feminist issues on social media.

Her award-winning novel ‘Asking For It’, which deals with the events before and after a seventeen-year-old girl is gang-raped at a party, raises important questions about consent, rape culture and the low prosecution rate of perpetrators of the crime – questions that are particularly relevant on any university campus.

According to a survey carried out by Union of Students in Ireland (USI) in 2013, eight percent of women said that they had been the victims of rape or attempted rape, while less than one percent of men reported being victims of rape or attempted rape. Of the 430 victims, less than three percent reported these incidents to an official within their college or university.

O’Neill talked to many people when researching her novel Asking For It including rape survivors as well as experts in the field, and recognizes that a part of her feels very strongly about reporting rapists and getting jail sentences because of this. But on a personal level, the 32-year-old understands why the reporting of rape is so low.

“The more that we report, the more that, hopefully, people will see jail time and it’ll have a societal effect in discouraging potential rapists. That’s sort of on a macro-level, on a societal level.

“On an individual level, when you’re talking to a friend of yours… it’s such a hard thing to try and tell someone to do. I think you need great reserves of – I hate saying strength because that sounds like you’re not strong if you don’t come forward – but huge reserves of self-will.

“It’s not fair to expect everyone, particularly someone who’s been violated in a really horrific way and is probably feeling very vulnerable, it’s not really fair to expect everyone to have those kind of reserves.”

One step she believes colleges must take is implementing mandatory consent classes for first year students – she believes it is their responsibility if they are committed to keeping their students safe.

“In most universities’ manifestos, it’s about providing a safe environment for all students to pursue academic excellence. I don’t think that’s happening and I think there’s a real issue with that. If we are looking at statistics that are coming out from the sexual violence centre or the rape crisis centre, the university campus seems to be the sort-of battleground for sexual violence at the moment.

“If you, as a university, are trying to protect students and trying to help them achieve their potential, then letting them just try and survive in a culture where sexual violence is nearly accepted as the norm…I just can’t understand how they would think that aligns with the values they have put forward in their manifesto.”

But O’Neill believes that the beginning of college is “a little bit too late” to be learning about consent.

“I think that it should be happening around 13 or 14 but the problem is there’s a real squeamishness around talking with teenagers of that age about sex, particularly in Ireland. So at least if you could get them at 18 and say ‘if someone is drunk they cannot consent.’

“Studies have shown that consent workshops do work, that they eradicate not all, but a lot of incidents of sexual violence, and that’s what we should be focusing on.”

As for other feminist issues the university should take a stance on, I ask her how she would feel if a Students’ Union referendum on the Eighth Amendment returned a neutral or pro-life result.

“I think that the Students’ Union should be campaigning for what’s best for the students, and maybe sometimes that might not necessarily be reflected in what a vote suggests,” she replies.

“I would find it really disheartening to see a students’ union say they were anti-choice.”

In November, the UCD student body elected a staunchly pro-life candidate as their SU President – something that O’Neill said she was still “in shock” over.

“You always think of students being really progressive and really forward-thinking.”

O’Neill is visibly frustrated with the outcome, going on to explain that she finds it “very hard” to take a neutral stance on abortion. She understands people being anti-abortion, but not anti-choice.

“I think it’s okay to say I am anti-abortion but I am pro-choice. I think that’s a really important distinction to make and to say that it doesn’t matter what your personal opinion is on this, you cannot exert your dominance over people’s life like that, and the thing is, if you don’t believe in abortion, no one is ever going to make you have one.

“This isn’t about morality, it isn’t about the ethics of it, this is misogyny. It comes down to a belief that you don’t think that women are fit to make their own decisions, that they don’t know what’s best for themselves, for their lives, for their bodies.

“When it comes down to that it’s very hard for me to stay neutral because I am like – either you believe that women should have control over their own bodies or they don’t. It’s as black and white as that.”

I wonder aloud what more students can possibly do to support the Repeal the 8th cause, aside from wearing Repeal merchandise or attending marches.

Last semester we had a feature in every edition of An Focal where we gave people the opportunity to write a letter to the Eight Amendment and voice their opinions on the issues. Aside from using your voice in this type of way, what other steps could pro-choice students around the country take to protest for full bodily autonomy?

“I’ve been thinking about it recently and I think it’s because I’ve been reading quite a few novels around suffragettes and it’s really – and I am not advocating this – but what I found fascinating was reading in these books they were setting fires, breaking windows, painting over letterboxes and being quite violent. They were jailed, they were on hunger strike, they were prepared to give their lives and they were completely ostracised.

“It is hard to be a feminist, it is hard to be a strong, vocal woman, you do get a lot of abuse, but it’s not the same.

“So, I don’t know, I am not suggesting we do anything illegal but I just wonder are we being slightly polite and taking a stance, or maybe waiting for our rights to be given to us.

“I think it’s about speaking up and demanding, actually, that those rights be given to us.”

![]()